A Short History of Stained Glass by Lizzie Plasom-Scott

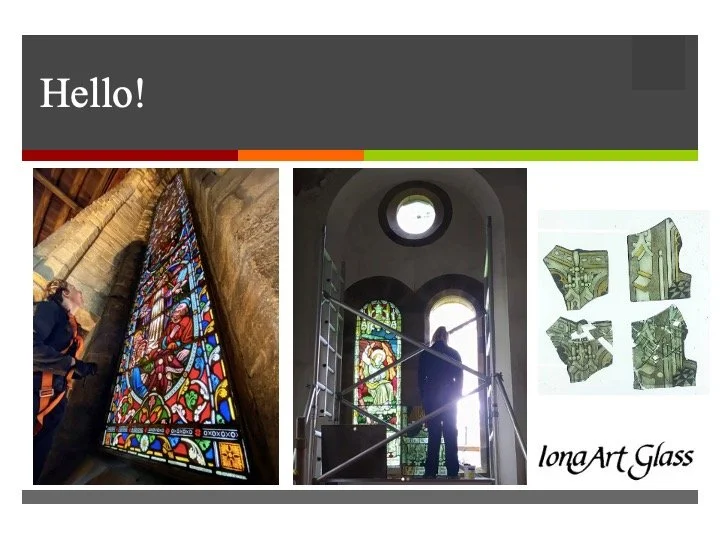

I’m an archaeology graduate from Durham university which is where I first really became interested in Stained glass, other than just admiring the pretty colours in the windows of the churches I attended. After graduation I started working at Iona Art Glass on the NE coast, just north of Newcastle. It is a workshop for the conservation of historic leaded lights. I’ve been doing that for four years now and I am honored to have been asked to speak at Our Lady & St Michael’s church in Workington to talk to you about the history of Stained glass and the practicalities of the beautiful works of art that we’re surrounded by and bathed in the light of in our beautiful churches.

I’ll start with a brief history of British stained glass and then move on to give you the practicalities of making and repairing these windows because that is what I do on a day-to-day basis – I’m not an art historian by any stretch of the imagination so I apologise to any historians out there! But I do have years of practical experience of stained glass to draw from which I hope will be of interest to you!

So… what is stained glass? Well actually it's a bit complicated because what we think of as stained glass windows sometimes don't even have stained glass in them; that's why when I was talking about Iona Glass earlier I referred to ‘leaded lights’ – but I’ll come onto that in a little bit.

First off- just a little bit of history:

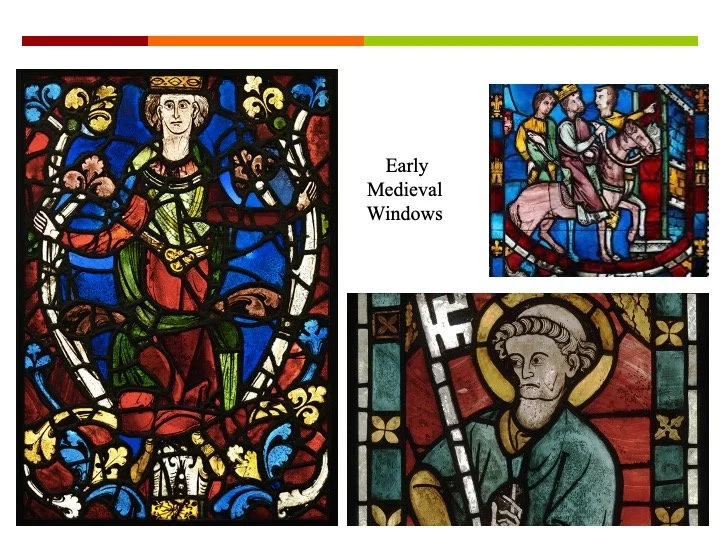

Stained glass has its earliest origins in Roman and Egyptian times with the earliest windows in Britain tracing back to the seventh century but it really took on its recognizable form today in the Mediaeval times, and that is hugely important for us in the study of these later windows. Early Mediaeval windows are typically small pieces of glass, very brightly coloured, leaded and painted to create small pictures of Bible scenes. The Medieval understanding of glass was very good though they were unable to get the larger sheets and uniformity that would come later. Their colours were jewel bright while not always entirely consistent with their composition of the glass itself, they were very striking and the Medieval age was the first boom of stained glass windows.

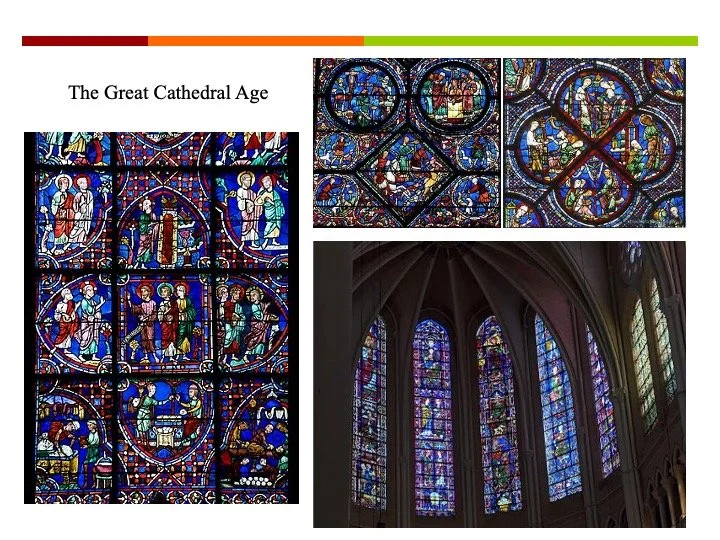

The Late Medieval to Renaissance period ushered in what is sometimes called the ‘great cathedral age’ with cathedrals such as Chartres in France containing some of the finest work of the period. It is at this point that technique was honed and the potential of stained glass to decorate places of worship was really appreciated.

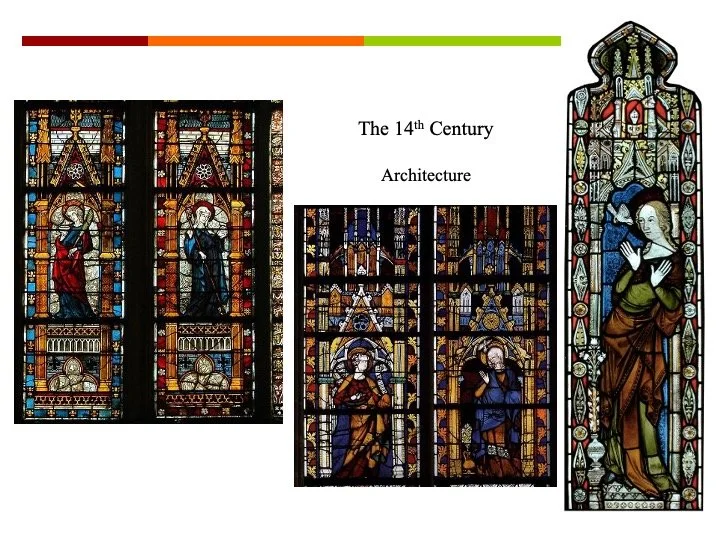

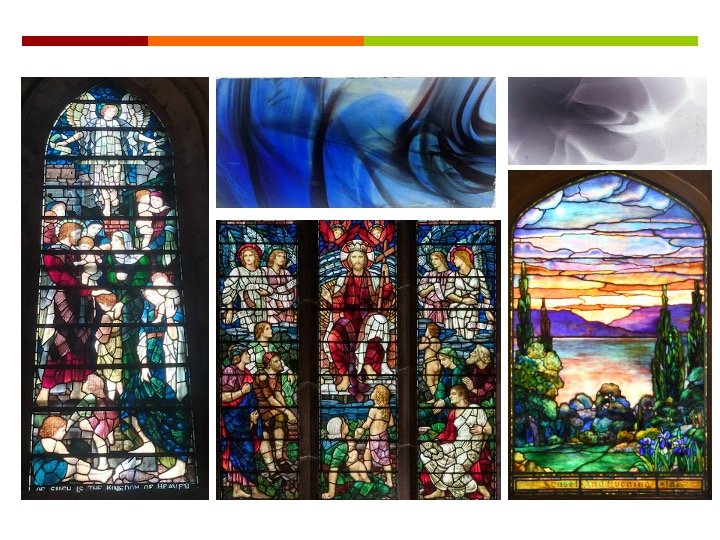

Of course the period that is of interest to us today in Workington is much later, in the 19th century, but it is important to realize that those Victorian artists were hearkening back to this ‘golden age’ of stained glass. As with so many aspects of Victorian lifestyle , they really idealized their past and tried to re-create it in their present. These Late Medieval Gothic cathedrals had much larger windows than their Romanesque predecessors. These wider and taller Gothic windows required different styles. The 13th century expanded outwards with story windows becoming the forefrontal type, with these big scenes displayed down the panels in separate categories and often across multiple lancets. However, by the time the 14th century hits, architecture has become fore frontal in window designs. Architectural canopies frame figures and scenes, occupying at least as much space as the figures and their verticality enhances the size of the windows as well as leading the eyes upwards towards Heaven. In the course of the 14th century these canopies became increasingly complex with niches and windows of their own sometimes filled with smaller figures and this intricacy became a definitive signpost of this period.

Now, as a result of the iconoclastic fury of the Reformation in England , we lost most of our historic glass – stained glass was a particular target for fervent Reformers who smashed images of saints and particularly images of Our Lady as these were seen as heretical.

Partly due to this destruction, and partly due to stiff European competition challenging English workshops, English stained glass then entered a period that has been referred to as the ‘dark ages’ for stained glass in this country as it suffered a serious decline in popularity throughout the 17/18 centuries.

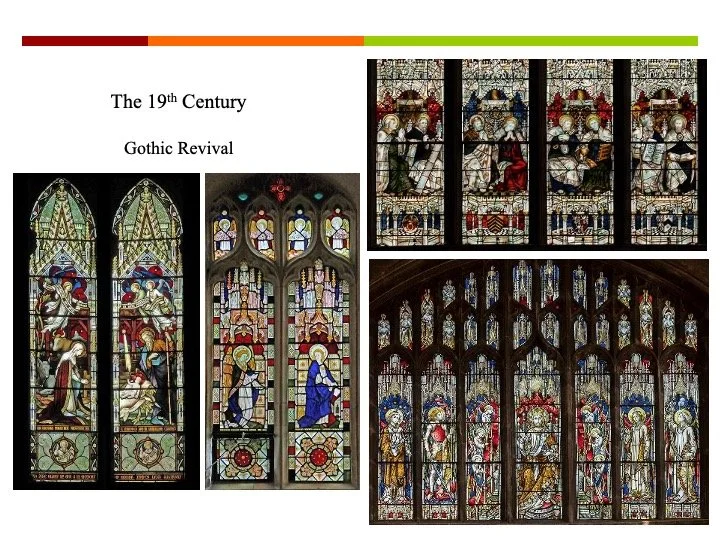

However, then came the 19th century! The century that we’re really interested in for this talk and this church. Early on in the 1800s, the Gothic style of churches surged back into popularity in architectural circles and this also prompted Gothic stained glass to come back into fashion to adorn churches. Europe, and England especially, were dissatisfied with the products of an industrial age and artists began to revere the crafts of pre-industrial times.

Demand for new churches at the time caused artists such as Augustus Welby Pugin to gain popularity. Pugin’s archaeologically accurate Medieval designs surpassed all other artists of the time – in the North of England the works of the likes of William Wailes can be seen widespread – indeed I am almost sick of them as they are the majority of the windows that we work on, it feels as though every other day we come across another brightly coloured Wailes window! However, Pugin, thanks to his extensive travels in Europe had a wide experience of Medieval stained glass and his understanding of the practicalities of the medium was more in depth than many designers. He was particularly drawn to that 14th century style that I have described, favoring the figure and canopy formula and attempting to fully recreate this classic Gothic look (though he did dress his donor figures in contemporary dress so he was not entirely sworn to only repeat the past).

One of the artists that you will definitely hear about later today is John Hardman, a Catholic who had an established ecclesiastical metal workshop in Birmingham and was encouraged by Pugin to take up stained glass in 1845. The pair collaborated, with Pugin as chief designer for the workshop, until his death in 1852. Their collaboration helped to foster a renewed love for stained glass in this period of Gothic revivalism.

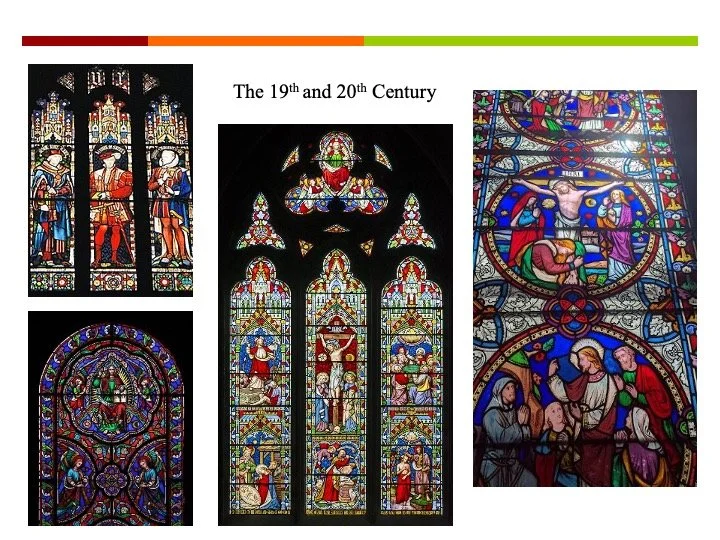

By the end of the 19th century, the styles of stained glass were much more varied than just the 14th century style advocated for by Pugin – the 12/13th century styles of those great Medieval cathedrals were often emulated but rarely were new forms of stained glass created - the Victorian period was really focused on emulating this earlier style and recapturing what had been lost for England. The success of artists such as Pugin and Hardman now threatened the entire medium with a creative infertility as the most prolific commercial firms turned to an industrial style of mass production in order to meet the massive demand for their products. In my line of work, we see a lot of these Victorian windows, created quickly and cheaply, a lot of re-used cartoons and designs where multiple windows could be easily churned out to meet the vast demand.

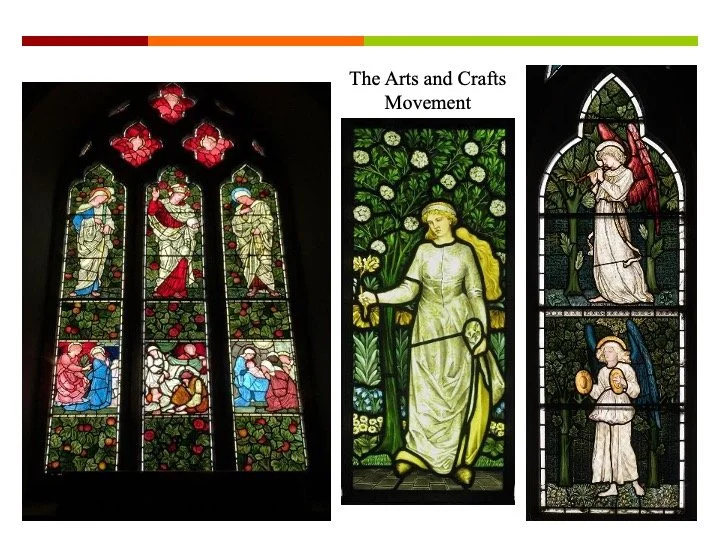

After this period, almost as a reflex from it, there was then a shift towards what is known as the ‘Art and Crafts Movement’ in design and decorative trends, which naturally was very influential in stained glass. William Morris was famously the forerunner of the movement in Britain as he rejected the archeological imitation of the Gothic and instead fuelled an enormous phase of creativity in English stained glass, favoring more natural colours, movement of figures and foliage-heavy backgrounds.

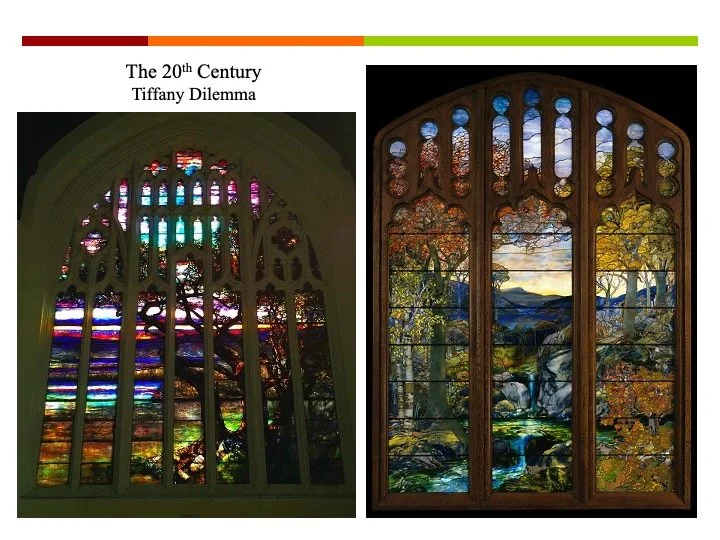

Moving into the 20th century, we begin to see the aesthetic dilemma of a new voice in the world of stained glass while churches and church architects continued to favour the Gothic style. Famous names such as Tiffany (know for his lamps) or La Farge struggled against this dilemma. The Russell Sage memorial window of Tiffany’s is a good example of this as he completely disregards the architectural style of the window tracery to create a stunning landscape window that uses his glass to full effect. This was a popular success at the time though loathed by the architect of the church who regarded it as irreligious.

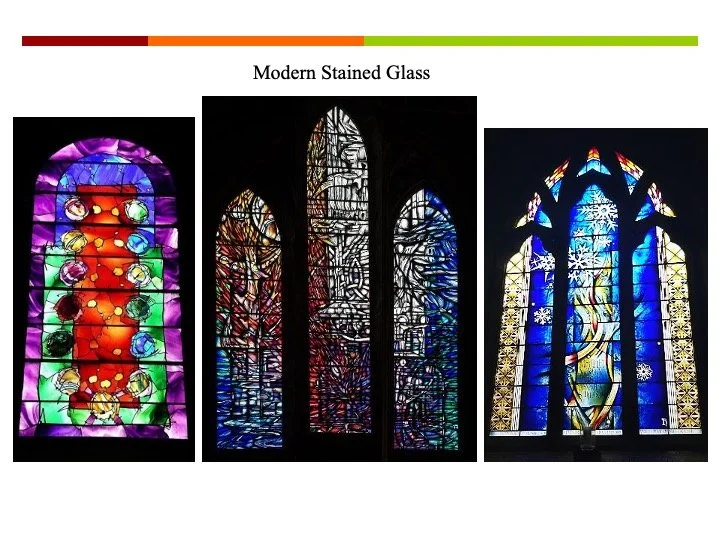

We then move into the world of modern glass where geometric shapes and abstract forms become more common, modern windows are typically less figurative and serve a slightly different purpose to their predecessors in that they tend not to instruct on biblical stories but rather create an emotion or feeling of religious fervor.

How to make Stained Glass

One of the fascinating things about stained glass is that the techniques used to create it have barely changed since its inception and widespread use in the Medieval period. So, here is a quick crash course on how a window is actually made.

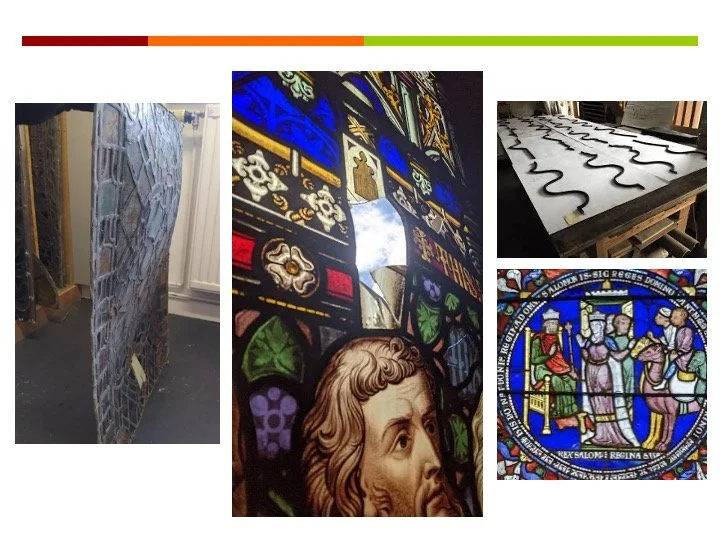

You start off, obviously, with your design. This is easier said than done as glass as a medium is pretty restrictive: there are certain shapes that are just impossible to cut out of glass, or at least illogical as they would leave such thin pieces remaining that the chances of them breaking are extremely high. Historically this would have been even more of a challenge than it is for us today. So once you have a design that is feasible, you decide on the colours that will be needed and you cut the appropriate glass. The majority of the colour from the windows comes from the glass itself, each piece being a different colour of glass. These pieces are then leaded into a lead matrix and soldered at the joins of the lead to keep it together. The lead lines are generally used to separate the different colours of glass, to enhance the design or simply because they are necessary to avoid unrealistically big pieces of glass or impossible shapes.

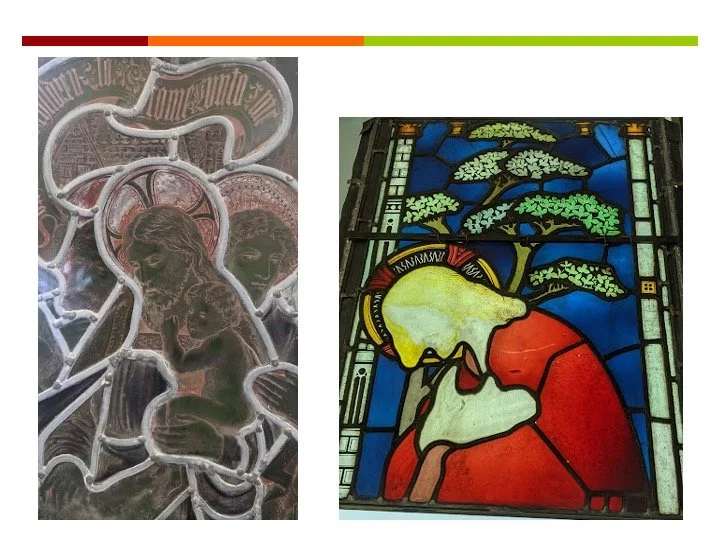

The intricate detail of the design is painted onto the surface. So the paint holds no colour, it simply provides detail and shading. It is painted onto the glass before the leading process, often in many layers and then fired at temperatures of about 660 degrees Celsius so that it fuses onto the glass.

This is the basic process for how a window is created; however you may have noticed that I haven’t yet mentioned stain, which is clearly an important feature!

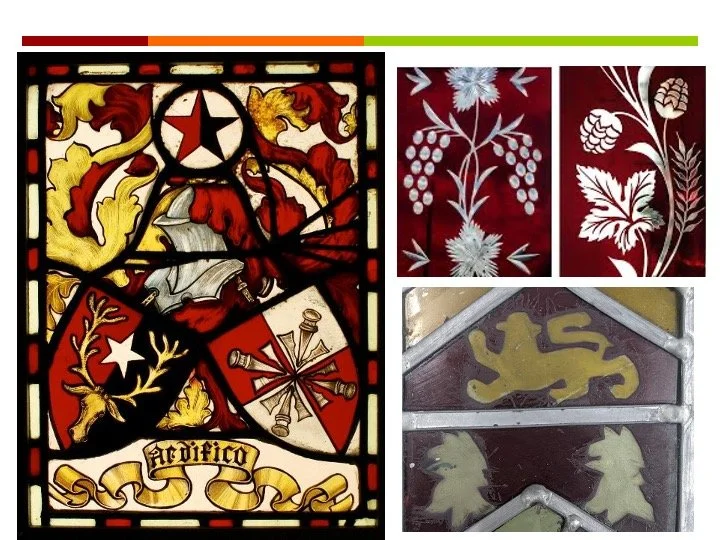

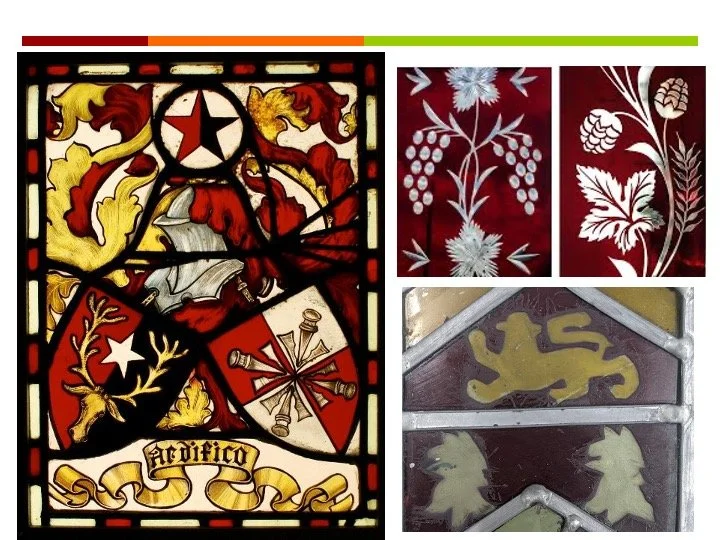

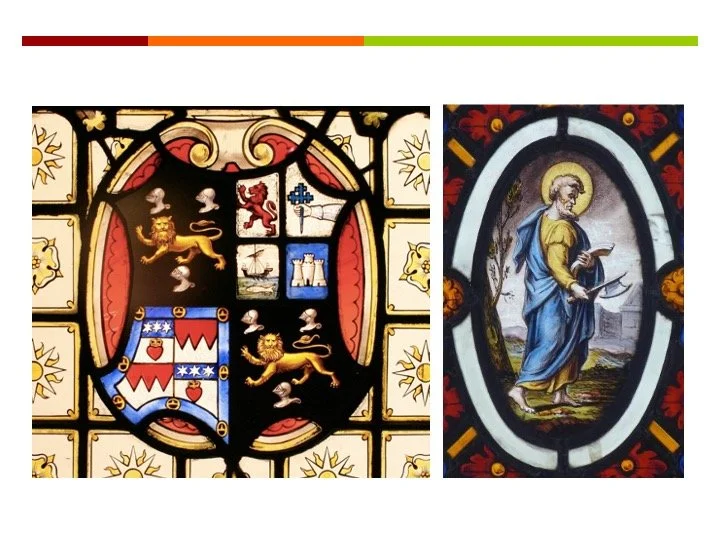

As I have described it so far, if you want a different colour, you have to use a different piece of glass separated by a lead line. However, stain changes all that –the first use of yellow stain has proved impossible to pin down but the Heraldic Window of York minster 1307 is the earliest surviving English example known. With the introduction of stain came the possibility of having multiple colours present on one piece of glass. The stain is applied to the glass like paint, fired at a slightly lower temperature (roughly 550 degrees) and chemically adheres to the glass in a way that alters the colour – on white (or clear) glass it turns yellow. It can be found in varying shades of pale yellow to a deep orange; firing temperatures can affect this with a higher temperature normally causing a deeper colour. It can also be placed behind pale colours, blue for example, and it would alter the colour of the glass to green. Stain can easily be spotted in hair, halos and golden decoration - all of which were used to full advantage in historic windows.

Along with this revelation came the use of what is called flash glass to allow further explorations into colour without the need for an overload of lead lines. Flash glass is clear white glass with a very thin layer of coloured glass fused on top, usually red or blue as they are easily malleable colours. It is then possible for this thin layer to be removed to allow a piece of glass that is partially white and partially coloured. Early instances of this have the coloured layer being forcefully scratched off the surface, but this would later develop into acid being used to etch off that top layer, and we currently use a sandblasting machine to create a similar effect. That clear portion of glass can then have stain added to it allowing for, say, a red and yellow to be present on the same piece of glass.

Enamels can also be used to add colour onto glass in small sections but they do not have the translucent quality of glass that the stain preserves and so, apart from a brief stint in the 17th century where Dutch roundels flourished in popularity and were heavily enameled, they are not as widely used.

With colour being so important some artists chose to blow their own glass and create their own colours – like Henry Holliday who created iconic thick slab glass in a range of unique colours and textures for exactly what he wanted. There is a beautiful example of his work in Hexham Abbey (restored by yours truly) where the colours are really remarkable (and the glass is insanely thick and difficult to work with!)

Other fun things to spot:

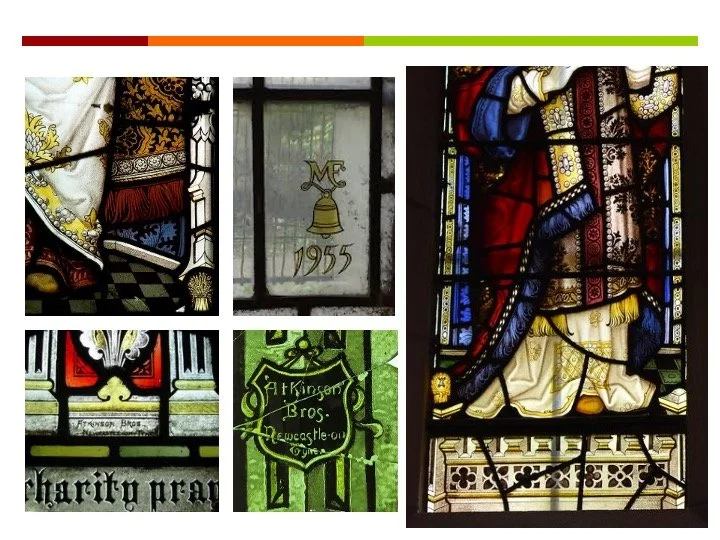

One fun feature to look out for if you're observing the stain glass windows is whether they have any makers marks. Just as stonemasons would carve into blocks to prove that it was their craftsmanship, stained glass artists signed their windows in specific pieces to show that this work was their own. Some artists such as Kempe (from the late 19th century) have very recognizable signatures that they incorporate into designs. His is a wheatsheaf that can be seen in the majority of his windows, whereas others simply sign their names.

It is also important to remember that stained glass is not just there to look beautiful or to tell stories of the church or the saints. While these are very important the windows also have an architectural function that cannot be ignored. Unlike most decorations in the church they have to withstand the usual stresses of a window. Lead is used for stained glass because of its malleability yet this also causes problems as gravity has an effect on the windows. I’m sure you will all have seen examples from churches where their windows have sunk under the weight of its own glass and lead. The more lead there is to create an infrastructure to the glass, the more weight there is pulling on the window. Metal (historically iron) bars are used across the windows to support it; the window is tied to the bar so that the weight can be supported by the bar and stonework. Most bars are made to work with the designs of the windows and so the artists hope that you tune them out and don’t notice their presence. It’s one of my pet peeves when a bar is placed badly in a window and ruins the design and I feel that since I have worked with stain glass they are always now one of the first things I noticed in the window so now you can all join in on that as well now I’ve pointed them out.

One of my favourite things about stained glass is looking at the designs and understanding how the artist has worked around the constraints of the medium with colour and shape being restrictive but also so important and to see how the artist pushes the boundaries of what they are able to do with the medium.

This has been a very brief crash course in both the history and the practicalities of stained glass, I hope there has been points of interest and that everything was clear - please feel free to ask me questions now or come up to me later to discuss, I have thrown a lot at you there but , my main hope is that now when you look at the beautiful windows we have in our churches, you can appreciate them for their storied history and the technical ability it took to make them as well as the images that they are depicting. Getting to conserve these storied works of art is a true pleasure of mine and I hope that they are appreciated by everyone as much as they are by you.